Musicianship

Rhythm - II. Pulse and Meter

1. Pulse vs. Meter

There are two basic concepts for rhythm: pulse and meter. They are related, but not the same thing. All music other than ambient soundscapes or pure drones will have pulse of some sort (and even some soundscapes can have pulse); while most music has meter, not all music does. Pulse is a steady beat that you feel. The pulse can change over time, but at pretty much every point it will be noticeable, at least subtly. Meter is a regular, recurring grouping of pulses, in such a way that it sets up recurring cycles of beats, called measures (or sometimes called bars - I use these terms interchangeably below). These can be organized hierarchically, so you can have subdivisions of a beat (pulse) at the lowest level, the beat or pulse itself, and then measures (or bars), phrases, periods, sections, and then a full piece of music, which might be complete by itself, or might be a single movement in a larger multi-movement work. This sort of analysis is the topic of study of form in music, which in music theory classes is called “formal analysis”. Meter can also change over time. Tempo is the speed of the pulse, measured in BPM, or “beats per minute”, and can be tracked with a metronome, which will tick at a steady speed. This tool is the bane of many performers as they practice, as it reveals when you are not keeping a steady tempo yourself(!), but it can be useful to try to get better at that. You can fall into a trap of relying too much on the metronome, and in fact in classical music (really in most music) we don’t want to feel too metronomic, but you want your variations to be intentional and artistic, and not sloppy because you can’t do better. Section 2.11 talks more about the metronome.

2. Time Signatures

There are several common meters in use in most Western music. The most common is probably 4/4. This designation is called a time signature, in this case pronounced “four four”, and means that “there are four beats to a bar (the top number) and the quarter note gets the beat (the bottom number)”. One way to remember the bottom number is to think of putting a one in the top number, or 1/4, which is one quarter [note]. This works for all time signatures. Anything with /8 will be an 8th note to the beat, /2 is a half note to the beat, etc. Any of our standard note types can get the beat, but the most common are /2, /4, /8, and occasionally /16 (half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note respectively). Of those, /4 and /8 are by far the most common. You can have any number of beats per measure, but again, some are more common than others. 2, 3, and 4 are the most common top numbers in general. 6 is common especially with an eighth note (6/8), but also appears not infrequently with a quarter note (6/4). I don’t think I’ve ever seen 6/2, and only now and then 6/16. Overall, 4/4 is the most common, followed by 3/4, 2/4, and 6/8.

3. Recurring Beat Patterns

Meter sets up a recurring beat pattern. You generally count them by counting up the numbers up to the top number in the time signature. So for 4/4, you’d say “1, 2, 3, 4 | 1, 2, 3, 4” etc. until you reached the end of the piece or the next time signature change. Here it is in notation (click here for a guide to reading rhythm in notation if you need a refresher):

You can have subdivisions within this. In 4/4, we usually divide the quarter notes into 8th notes, and we count this by saying “1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and, etc.” The “and” is the “offbeat”, or the 8th notes between the main beats, which fall on the quarter notes. You will sometimes see the “and” written with a + to make it easier to read: “1 + 2 + 3 + 4 +” etc. You will say it the same way. In notation:

We can break the 8th notes into two 16th notes each, and then we get “1e+a, 2e+a, 3e+a, 4e+a” for our count:

There are four 16th notes for every quarter note:

Below that I don’t have a good phrase to say, but it’s relatively rare that we encounter notes less than a 16th note (see Beat Slashes for Ease of Reading for help when you do run into that).

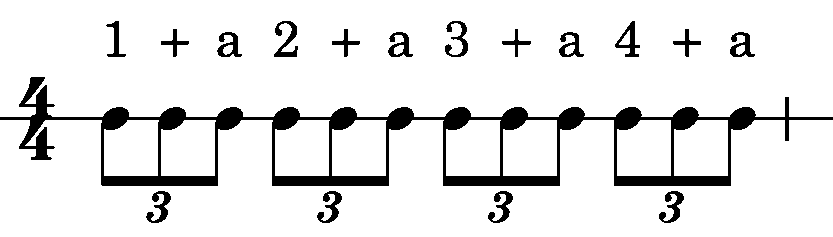

We can also have “triplets” or more generally “tuplets”, which pack other numbers of subdivisions in a beat. A triplet puts three in a beat, so we have “1+a, 2+a, 3+a, 4+a” (spaced evenly throughout the beat).

One thing that often trips up students when they are learning to read and count rhythms is to keep a distinction between triplet and 2 or 4 rhythms (and even in my semi-pro ensembles we still occasionally have to talk about this). One frequent issue is dotted 8th/16th note patterns, which often get “lazy” and become a kind of triplet (quarter-note eighth note triplet). Make sure you count three 16th note ticks for the dotted 8th note and place the sounded 16th note on the fourth one:

The other frequent issue is mixing up triplets and a common syncopated pattern (see Rhythm Cells in the next chapter, and Syncopation a little later in this guide). The pattern of one 16th note, one 8th note, and one 16th note needs to feel distinct from the triplet pattern, especially in certain styles like tango or the habanera, where they might use either of those rhythms and you need to know which you are using. Really make sure that your triplets are even! See the following notation / audio for some examples.

Just to make things even more confusing, in some styles notation is used loosely anyway - in Irish fiddle music, if you are playing a reel, a triplet should be played like this:

Or even tighter, like this:

But in an Irish hornpipe, or in a Scottish march, triplets are played more evenly. So you have to know your styles, but if you are playing most styles, and especially classical music, really make sure your triplets are even in 3 and your dotted notes are tightly counted 4s, and play syncopation distinctly as well. In CSUN’s musicianship classes, I’ve been tutoring some fairly complex rhythm training and one major point they are making with these drills is distinguishing all of those rhythms with precision.

Other tuplets include “quintuplets” or 5 divisions per beat, and any number is in theory possible. Really extreme examples of tuplets can be found in the fioritura in Chopin’s Nocturnes and other similar pieces - these are long sequences of notes that fit into what seem like shorter note values and give an ornamental effect. Here’s an example from Chopin’s Postumous Nocturne in C# minor, near the end of the piece. Each of these fioritura fit inside a half note of notated time. In this performance, he does stretch the timing of the longest one a little bit (see Tempo Fluctuations in Classical Music for more)

4. Hierarchy of Beats and Phrasing

The next point about Meter is that the beats themselves are hierarchical, so in 4/4, we usually describe it in one of two ways. The most common method you learn initially is to say “the first beat is the strongest, the second beat is weaker, the third beat is between them (stronger than two but not one), and the last beat is the weakest beat”. Another way to think about this version is that there are two sets of “STRONG weak [STRONG weak]”, and the second set is overall weaker than the first set. I actually don’t really know how often I use that approach in practice. The other approach which it feels like is more often the way I play is to say “the first beat is the strongest, then we drop off for beat two and build up to the next downbeat (beat one)”. Either way, this is a subtle effect and you don’t usually have a noticeable accent like this. If you did the piece would feel far too “notey”. This is more of a concept to keep in mind rather than a way to really play music. In some ways it’s almost more useful for composing when you are thinking about structuring music than it is for performing that music in sound.

One other thing to think about in this regard is that meter can be accented in multiple ways. We tend to think of a volume accent when we think of accents, but harmony is also a type of accent. In much of our music, the harmony changes on beats one and three (see Harmonic Rhythm below), and this gives some of the accent to emphasize those beats so that you don’t have to “play” an accent on those beats. Chuck Israels notes in his book Exploring Jazz Arranging that:

In jazz and most popular music, harmonic changes take place on the first and third beats of common time (4/4) music. The accents on the second and fourth beats in jazz function to balance the emphasis that accrues to the downbeat as a result of the changes in harmony, and should be played as strongly as they need to be to fulfill that function and no stronger. Accenting the second and fourth beats, as so many school musicians are taught to do, only serves to unbalance the music in the other direction and is as destructive to the swing as overemphasizing one and three. (page 7 in my edition, which is an older version of the book).

So the music will have some of this hierarchical feel without putting strong accents in it yourself.

Once we have a few bars of music, then we can start to add phrasing across bars, and this is usually more noticeable in sound. In this context, we will start applying a few different ideas, one of which is to grow into tension and relax out of it (see Life Tips Composition Tip No. 24). You can also try growing as pitch rises (if you have an ascending scale, get louder, for example), and relaxing as pitch falls (as the scale descends). There are many other ways to phrase a passage, but one thing to keep in mind is that if the notation does not call for dynamic change, then all of this should be subtle “natural phrasing”, not really obvious dynamic change. It should only be obvious if the notation explicitly calls for it.

Here’s a fun example showing some phrasing. This is the second movement of Russian romantic composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony, an unusual 5/4 waltz (see “Odd Meters” below for more about counting in 5/4, and note that waltzes are usually in 3/4). For now, notice how the opening line grows as it climbs at the beginning, and then on the last measure it relaxes as it falls in 8th notes from the high point (m.8, 3rd measure on page 2). This is marked to some degree in the dynamics, though in this performance they keep phrasing even when it doesn’t say so explicitly, which is what they should do. But the overall shape is marked by the dynamics.

For this next example, we’ll turn to the keyboard pieces of J.S. Bach from the German high Baroque, and look at the Prelude No. 1 in C Major from his set called “The Well-Tempered Clavier” (this will be from book 1 for people keeping track at home). I have chosen a video from Lang Lang as he plays in a very expressive manner in this performance, so you can really hear the phrasing clearly. In some performances of this piece, they try to keep things mostly the same with only very slight phrasing. I said above that if there’s no dynamic you should only use subtle “natural expression”, but in music from this period, they mostly didn’t write dynamics into the keyboard sheet music for a few reasons, one being that they had several keyboard instruments and each would use different expression (none were the modern piano, by the way). See my essay “On Interpretation and Notation in Music” for more on this topic. On a modern piano, you can add modern piano expression just like back then they would have added expression appropriate to the instrument they happened to be playing, which could be the clavichord, the harpsichord, or even potentially an organ. Check out this pair of videos from the Music Institute of Chicago’s David Schrader for more on those instruments if you are interested (by the way, the MIC was the main music school I attended outside my actual school when I was a kid learning violin and my early musicianship classes, as well as some of the orchestras I played in growing up, and I’ve played several times on the Nichols Concert Hall stage in Evanston, IL that those linked videos were filmed on).

For our purposes today, I’m going to feature the ending of the piece, so I’ll provide sheet music starting on the dominant pedal in m. 34 (in the video, this starts at 1:27). Note that the video plays from the beginning, as it’s a short piece and then you can appreciate this in context. We have several bars (specifically mm. 34 to 41) where we sit on a dominant (G) pedal, and every time we think Bach is finally going to resolve it he delays it again, building up the tension to extraordinary levels for a relatively simple piece like this. When he finally does “resolve” it down to C, he once again tricks us and makes it a dominant seventh chord instead of a tonic I chord, so it becomes V7/IV, allowing us to go around one more time from IV to V7 with a tonic pedal, to I only on the very last chord.

Lang Lang phrases this section by dropping to a very soft dynamic to start the build on the dominant pedal (m. 34). Then he gets huge by the climax in m. 39, drops the tension slightly after the peak of the phrase and a bit more when the G pedal resolves down to C. He keeps some tension since we still have one more IV V I cycle, and it finally relaxes fully into the final I chord.

5. Duple vs. Triple, Simple vs. Compound

Duple vs. Triple, Simple vs. Compound: You will hear about “duple” meters and “triple” meters, as well as “simple” vs. “compound” meters. Duple vs. triple refers to whether there are two or three beats per measure (I don’t usually hear about quadruple meters in this context). Simple vs. Compound is whether the beats are divided into two subdivisions or three subdivisions. “Simple Duple” is 2/4, “One + Two + | One + Two +”. Compound Duple is 6/8, “One+a Two+a | One+a Two+a” (1,2,3,4,5,6 1,2,3,4,5,6 with accents on 1 and 4). Simple Triple is 3/4, “One + Two + Three + | One + Two + Three +”. And Compound Triple is the most common version of 9/8, “One+a Two+a Three+a | One+a Two+a Three+a”.

6. Counting Subdivisions

When counting any meter, you need to be counting in subdivisions. Every meter has “big beats” and subdivisions. Sometimes the time signature is wrong, but you still have this overall concept. The big beat is what you count when you say the main numbers, and then additional syllables would be subdivisions. There are several layers of this, and how you say them can shift, but this is the basic idea. Irish Reels are an example of a type of tune where the meter is usually wrong - they are usually written in 4/4 but usually felt in 2/2 (2 half note beats per bar), with 8th notes as the common subdivision so that you have 4 subdivisions per beat. Between them you have quarter notes, which you will also usually feel as a separate layer.

You want to count everything in at least the smallest subdivision you actually have in the sheet music, and it doesn’t hurt to go one more level deep. If you mostly have quarter and eighth notes, you can count in eighth notes, but it wouldn’t hurt to be thinking of 16th notes. I try to encourage my musicianship students at CSUN to count subdivisions when we’re working on rhythm for dictation. And at first, when you are reading music or counting something you are listening to, you should say the words out loud. Later you can say them “out loud” in your head, and eventually you will internalize them in such a way that you don’t have to say the words in any form, but you will “feel” the beat (subdivision) internally. If you get more complex rhythms, you may need to go back to counting out loud to figure out what it is you are dealing with, and that’s completely fine! I still sometimes count out loud when I’m looking at something and am struggling to get it right. However you consciously do it, you need to be aware of subdivisions, not just the main beat.

Note that once you are getting this as an internal feeling, you will be feeling several layers at once. I was recently working with one of my tutoring students on musicianship rhythm practice, and we were looking at 6/8. I showed how we could have three layers here with the metronome ticking in dotted quarters as One, Two, One, Two, then I would initially feel “One + a, Two + a” (or “One, two, three, Four, five, six”) for the 8th notes and then within that I was feeling “Ticky, ticky, ticky, Ticky, ticky, ticky” or “One+two+three+Four+Five+Six+” on the 16ths level. I wouldn't normally say the 16ths out loud, but I would feel that groove. I can then jump back and forth across all these patterns as desired without ever losing track of the groove, but whichever layer I'm consciously aware of, I am feeling that 16th groove the whole time at least subconsciously. Again, it's more of a feeling in my body rather than words in my mind unless I really need them to be. But keeping this groove going, this “Rhythm Matrix” as Phil Best calls it, allows me to accurately place the rhythms we are playing or practicing in precisely the right spot to get a strong groove going. I’ve prepared a video myself to demonstrate some of these points, and I talk about this in “real-world” examples in other sections as well (see for example the next section below on “Odd Meter” for Sensemaya, which demonstrates this phenomenon very clearly in the writing directly).

7. Odd Meters

“Odd” meters exist as well. 3 is very common, and not considered one of the “odd” meters, but 5, 7, and 9 are all found sometimes in the top number (even 11 and 13 can be, and so can others but they aren’t as common). These tend to throw people when they come up, particularly if they haven’t been taught to count them properly. They will usually be divided into “shorter beats” and “longer beats”. 5 is generally either 2+3 or 3+2 (“One+ Two+a” or “One+a Two+”), 7 is usually 2+2+3 or 3+2+2 (“One+ Two+ Three+a” or “One+a Two+ Three+”). Nine is most often 3+3+3 as mentioned above.

A couple of things really helped me cement my feel for “odd” meters. I got to play a piece called “Sensemaya” by Silvestre Revueltas in orchestra two years in a row - my last year at New Trier High School in Symphony Orchestra, and my first year at Berklee in the Berklee Contemporary Symphony Orchestra. If you get a chance to play the piece, it will do wonders for you, and if you can even just listen to it a few times it might help as it has such an infectious groove. Just listening with no score may not be as useful though, as the meter changes frequently. That’s why the video I’ve chosen below features the score. This piece really helped me get a solid feel for 7/8 (particularly in its 2+2+3 form, which is what Sensemaya uses). The most interesting meter in Sensemaya is a spot at the climax near the end (4:45 in this video) where he uses “5.5/8” which throws everyone completely when they first see that! Today he’d probably use a “compound time signature” and call it “1/4+7/16” or “2/8+7/16” as that’s what he’s actually doing there. Or he could call it “11/16”, but the compound time signature would be more effective there.

This also is a great example of the point immediately above this one about counting layers of subdivisions and will give you a good sense of what that should feel like and sound like, as Revueltas actually writes them out in this piece (note that most pieces don’t write them so clearly, but you should still be feeling them). From the very beginning, you get both the “big beat” groove and the smallest subdivision, between the tom-toms / bass drum, and the bass clarinet. Four bars in, the bassoon starts playing the middle layer with steady 8th notes in a repeating pattern, and from that point on in the first big 7/8 section (approximately the first three minutes of this recording), someone in the orchestra is always playing each of those layers. All the other parts get slotted into their respective places in that overarching groove or matrix.

The other thing I got to do in my first semester at Berklee was String Improv class with cello professor Eugene Friesen, which was all about cross-rhythm and really helped me learn those cold, and we explored odd meter there too to some degree.

8. How to Choose a Beat Value

How do you decide which note value to use for your beat? With different tempos, you can make any note value for the beat sound the same, so it’s not necessarily clear which to pick. In general, the way you decide which to use is the overall feel you want. All else being equal, shorter note values will make the music feel lighter and longer note values will be heavier. So 3/8 is pretty light and good for a light dance feel, 3/4 is pretty “normal” feeling (and is used for many triple meter dances), and 3/2 will be somewhat heavier and more ponderous. It’s not a hard and fast rule, and ultimately it’s pretty subjective, but that’s the general guidance given.

A couple of examples to demonstrate this from the romantic period orchestral repertoire. 3/4 is so common that I’m not going to bother finding an example here. That designation can be used for any mood anyway, and I could find a “normal” feeling example, and you could go and find a lighter or heavier one just as easily. But 3/8 and 3/2 are used largely when the composer really wants the extra effect that those designations would give, so here’s a 3/8 example.

This is the (in)famous Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s music to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”. I call it infamous because it is on the professional orchestral audition excerpt list for several instruments, including one of my primary instruments, the viola; so anyone who is a classical performance major on those instruments should be intimately familiar with this piece! For our purposes, note how fleeting the music feels. It is very light and airy, and this would be one reason to use 3/8 for this piece. It would be possible but more difficult to achieve a similar feel with 3/4 - it really does make a difference.

Here’s an example of a piece that uses 3/2 (and eventually 4/2). This is the 4th movement of Robert Schumann’s 5 movement Symphony No. 3 in Eb Major (the ‘Rhenish’). This example starts in C[ommon] time, effectively 4/4. A few bars in (at 23:17 in this video), they get to the 3/2 section. You can hear how much weightier this movement is than the fleeting 3/8 we heard in the Mendelssohn Scherzo above. The german mood indicator at the top of this movement “Feierlich” means “Solemnly”, and the German text above the 3/2 “Die Halben wie vorher die Viertel” translates to “The halves like the quarters before”, which makes this a textual version of a metric modulation. He could have written this passage in 3/4 with the note values halved and it would have had the same tempo effect, but he really wanted the portentous weight of the 3/2. The Wikipedia analysis of this movement notes that “…the trombones have yet to play at all until this point”; and the solemn designation, the trombone entrance in this movement, and the counterpoint here would all combine to give this a very religious feel to the audience at the time it was written (did you know that trombones were originally primarily church instruments, and that one of their first uses in a symphonic context was only a few decades prior to this in Beethoven’s 5th symphony?).

9. Compositional Phrasing (Form)

This is a concept for composers and arrangers more than for performers, though as a performer you will notice this phenomenon in pieces you play. But as a composer or an arranger, you will be able to decide how to set up phrases in your music. Here we’re talking more about form than about expression. The most common phrase structure in a lot of styles of music is to use 4-bar phrases, usually grouped in pairs into 8 bar phrases that make up sections of pieces. In many fiddle styles, for example, tunes usually have two 8 bar phrases, each of which repeats (possibly with different endings each time), for a total of 16 bars per section and 32 bars for the tune. Some tunes will have three parts, or even four parts, so you’d add 16 bars for each part to get the total for the tune. This structure works well enough, but it can get boring if that’s all you ever do. In fiddle dance music, the music is (at least in principle) functional, meaning it’s music for doing something else, in this case, dancing to. So keeping the phrase structure boring but predictable is more important than making it really interesting.

In other kinds of music that aren’t intended for dancing to (or something similar), it can be good to change up the phrase structure from time to time to keep the music interesting. There are lots of ways of doing that, but two of the most common are the deceptive cadence, and “odd” phrase numbers. These can show up in all kinds of music.

A deceptive cadence is a harmonic tool in tonal harmony or related types of harmony. Usually in tonal harmony the V chord (five chord) resolves to a I chord (one chord - major in this case, or minor if it said i). If a V chord resolves to any other chord, it’s a deceptive cadence, and the most common version is to resolve to a vi chord (six minor chord) in major key, or a VI chord (six major chord) in minor key harmony. This then sets you up to go around a chord progression one more time and end with a V to a I (or i) chord, frequently in a perfect authentic cadence to end the piece. Using this technique you can extend your phrase from 8 bars to 10 or 12 bars and make it a bit more interesting. Here’s a guide to the music theory if you want to explore cadences further, with some examples from the classical and pop repertoire.

Another way to make your phrase structure more interesting is to add some extra bars between sections that otherwise might run together. I ran across this example recently, which I think is worth exploring in some detail as it shows several interesting points, and not just on this topic. This is a track from the latest album by the Celtic band The Barra MacNeils from Cape Breton, Canada. They have a rather unique blend of Celtic folk and pop music, and this track leans pretty heavily towards the pop side of the spectrum, with a very catchy groove. It’s a satirical song on modern life called “Living the Dream”, from the album On the Bright Side. Here it is, and then we’ll explore it below:

To connect it back to the topic in this section, we can look at just the opening of the track. The first part is a standard 4 bar phrase in 4/4, but then it gets expanded by two beats on the last note (the word “why”), and then there is just one bar after that between the first verse and the second verse. Then after the second verse, they don’t expand the last measure, but again there is only one bar between sections. So arguably we have two 5-bar phrases, with the first one being extended by two beats.

Another thing to notice about this track overall is that it isn’t particularly melodic. Here is notation (my transcription) of the first verse:

As you can see, it’s pretty much one pitch, just the tonic (the first scale degree), G. It does have a couple of other pitches now and then as pickups into each line, but we’re basically sitting on one pitch and droning for the “tune”. The chords are not particularly interesting here either - this is a very “droney” opening, which is somewhat meditative in that sense. The tempo is pretty fast (the active groove is based on 16th notes here, so it feels faster than the q=80 in the metronome mark might suggest). The main interest in this part comes from lots of syncopation in the melody, and from the words to the song. A lot of pop songs are like this, where the words are what give the interest to the song (or maybe the textures of the backing track) - if you made them into instrumentals where the melody was played by an instrument, the song wouldn’t really work very well. As we get further into this song, the melody will start to pick up slightly, in the pre-chorus (or maybe the first half of the chorus depending on how you want to label it), for example - the part starting with “Everybody needs…”. But it’s not really a melodic song.

As we move through the song, they continue to add beats or use 1 or 2 bar transitions, and also play with dropping the backing instruments in a few well-timed places. Then the chorus is used as a spacey bridge, where they add an organ pad and lots of reverb (and some EQ-effected vocals) - 2:55 in the track. Finally, they bring back the first verse at the end of the track, and end it on the IV chord (C major), ultimately making a very effective pop song!

10. Harmonic Rhythm

Harmonic Rhythm is another compositional concept. The basic idea of this is how often your chords change in your piece. Composers can change the harmonic rhythm throughout a piece to change the feel or mood - fast harmonic rhythm will tend to feel more intense, slow harmonic rhythm will tend to relax. In the Barra MacNeils example above, the harmonic rhythm is slow in this opening section I’ve highlighted - the chord doesn’t really change at all until the extra measure at the end of that verse.

In this section, I’m going to look at three types of pieces with harmonic rhythm: Chorales (fast harmonic rhythm), “typical” folk songs (medium harmonic rhythm), and drone songs (slow harmonic rhythm, though note that these will not be pure drones, and they will still have significant movement).

Chorales

A Chorale is a type of music originally found in a church setting, usually setting hymn text to music in a way that a church choir or the congregation can sing it. The most famous chorales today are by J.S. Bach, who wrote over 300 chorale settings of German Lutheran Hymns. These have become models of four part harmony, and if you’ve ever taken a college harmony class, you will be thoroughly familiar with the concept and quite possibly with at least a few of the Bach chorales. I had to analyze some of them in my classical harmony classes at Berklee, and I’ve been tutoring some of the CSUN undergraduates in their harmony classes, and some of that has involved analyzing chorales.

The main musical point in this context is that these are pieces where the harmony changes on pretty much every beat, which makes it a fast harmonic rhythm. Mostly it follows the rhythm of the melody, with all four voices changing notes together. Once you get out of basic classroom mode and you look at real chorales, you find that the rhythms change slightly between voices so the music has a little bit of rhythmic interest as well as harmonic interest, but most of those rhythm changes lead to non-chord tones, so the harmony still stays moving at one chord per beat rhythm. Here is an example of a Bach chorale that you may or may not know. This is No. 1 in the collection I’m using. I’ve analyzed the harmony to show the chords moving more or less one-per-beat (this isn’t a music theory course, so don’t worry if you don’t know what all the roman numerals mean. The point is to note that there’s about one per beat. If you want to know more about harmony itself, here’s a free online guide I’ve found helpful for some of my tutoring work: Music Theory for the 21st Century Classroom)

“Typical” Folk Songs

Coming soon!

Drone Songs

Note that this doesn’t refer to drone tracks per se, which can be anything from a single pitch that hangs there for several minutes to a more complex soundscape track which has some movement but still sits on one key (or at least one open chord). There is exactly no harmonic rhythm in those kinds of tracks. But there are songs that have more movement but nonetheless have a very slow harmonic rhythm, and here is an example I’ve run across in my collection. This one is also from the Barra MacNeils, just like the track I analyzed in the section above this one. This time I’m showing “Seallaibh Curaidh Eoghainn” from their 1995 album The Question. The version I’ve pulled is from their compilation album 20th Anniversary Collection Album. Here it is:

As you can hear, this is a rather meditative and dreamy track (I promise not every track by the Barra MacNeils is meditative and dreamy!), and one of the big things that leads to that feeling is the harmonic rhythm in this track. They sit on the opening Eb chord for quite a while (16 measures), and even once they get into the main part of the song, the chord only alternates between Eb minor (though mostly a pretty open, modal sound, and in fact some instruments are playing G naturals for Eb major) and Gb major every 8 bars. There are only two chords in the whole piece and they each last for a long time as they alternate. Note that there is a groove to this track, so it doesn’t feel dead, but the groove is mostly playing the same note in a more active rhythm, and at least is not changing the chord. This is another good example of subdivisions (see Counting Subdivisions above). I’m feeling this track as a slow 2/2 (two half note beats per measure), subdivided into four 8th note subdivisions each, so effectively a reel dance rhythm. This would be more of a slow reel, as the half note tempo is about 82 bpm, whereas the full dance tempo is closer to 120 bpm for the half note.

This song is a type of music called “Mouth Music” in Celtic music (Port à Beul in Gaelic). It is a form of “nonsense” song, mostly trying to find words to fit a dance rhythm. In the case of this kind of song, they used real words and grammatical sentences, but it’s similar in concept to scatting in jazz and related styles. “Lilting” would be even closer to scat, where they use nonsense syllables that don’t mean anything, just to sing the dance tune. Old-time Americana also features similar nonsense songs to this one, where the words are grammatical and have meaning but just aren’t that meaningful as sentences. In other words, if you read the words to this song you’d wonder why anyone would bother writing a song with those lyrics, and the answer is mostly so they have something to sing! For reference, here are the words to this song:

O, seallaibh curaigh Eòghainn,

Is còig ràimh fhichead oirre.

Seallaibh curaigh Eòghainn

'S i seachad air a' Rubha Bhàn.

O, seallaibh curaigh Eòghainn,

Is còig ràimh fhichead oirre.

Seallaibh curaigh Eòghainn

'S i seachad air a' Rubha Bhàn.

Bidh Eòghann, Bidh Eòghann,

Bidh Eòghann na sgiobair oirr',

Bidh Eòghann, Bidh Eòghann,

'S i seachad air a' Rubha Bhàn.

Bidh Eòghann, Bidh Eòghann,

Bidh Eòghann na sgiobair oirr',

Bidh Eòghann, Bidh Eòghann,

'S i seachad air a' Rubha Bhàn.

Oh, look at Ewan's coracle

With twenty-five oars on her.

Look at Ewan's coracle

And she is passing the White Point.

Oh, look at Ewan's coracle

With twenty-five oars on her.

Look at Ewan's coracle

And she is passing the White Point.

Ewan will be, Ewan will be

Ewan will be the captain on her,

Ewan will be, Ewan will be,

And she is passing the White Point.

Ewan will be, Ewan will be

Ewan will be the captain on her,

Ewan will be, Ewan will be,

And she is passing the White Point.

11. How to Think About the Metronome

As I’ve been tutoring musicianship classes at CSUN, I’ve noticed that there seems to be some confusion over how a metronome works and what you can do with it. There are two versions of this: how to think about a metronome as a device, and how to use it to help with your practice. There are plenty of videos and articles online that go over ways to use a metronome to help with practice. Here are a couple of resources I’ve found useful. Nathan Cole made a video called “5 rules for metronome practice” for violin (though these rules apply to most instruments). Robert Estrin at Living Pianos has a video for piano called, conveniently enough, “How to Practice with a Metronome”. Graham Fitch has tips for metronome use in his ebook series Practicing the Piano (in book 1: The Practice Techniques)

But this is not the version I want to focus on here. I’ve found that some of my students are struggling with a basic understanding of how to think about the metronome. This seems to mostly be caused by using fancy metronome apps on their smartphones, which might in some cases be too sophisticated for their own good. When I grew up learning music (way back in the 1990s and early 2000s!), we only had a standalone metronome box that made a single ticking sound and had a red light that flashed in time. Then we could change the bpm in single bpm increments, and that was it. There was no accenting the downbeat, no worrying about whether we were in 4 or in 3 or this was the dotted quarter note or the quarter note or the eighth note. All of that came from how you mentally thought about the single ticking sound.

Later we got a Dr. Beat metronome, one of the first of the more sophisticated metronome boxes. This was still a standalone device, and at the time it cost about $100! But it added the ability to tick with different sounds in subdivisions (8th note, 16th note, every other 16th note, and triplet), and you mixed all of these in with volume sliders. This helped me to learn 3-against-2 polyrhythm by mixing in both 8th notes and triplets together. You could also have it accent every so many ticks (what “meter” you were in), and you could set that separately. Today, many apps exist for free or for a dollar or two that can do various things like that, and most people seem to use them by default (see below for what I use).

I’m not necessarily advocating going back to standalone devices (though I’ve done workshops with teachers who do - some of them say your smartphone has no place in your practice room!). But I am advocating a more thoughtful approach to using the metronome. You can do everything you need to do with a metronome without any of the fancy features you find on apps, many of which are turned on by default.

One particular feature that can be problematic is the accent for all downbeats. This is only useful if the passage you are working on is in the same meter the whole time. Admittedly, this is often the case, but we’ve been working on exercises that change meters at CSUN, so we have to disable the accent anyway. This also can tend to lead students to think of the ticks as meaning something specific about the notes they represent, when they are actually just sounds. This leads to the other issue.

The other feature that seems to cause issues is the description of meters. Students get hung up on the idea that the metronome is in 4/4 (or in 3/4, or whatever it says), and they wonder how to make it play dotted quarter notes instead of quarter notes. The answer is generally to shift how you think, not to change a setting on the metronome itself. If you are just using single ticks and not having the metronome itself play subdivisions with different sounds, then you just shift how you interpret them. You think in subdivisions of 3 rather than 2 or 4, and magically the metronome is ticking in dotted quarters instead of in quarters. This is where the idea of simple vs. compound, and duple vs. triple meter comes in handy. If you want to use the accent beat, and you want to do 6/8, you can set it to 2/4 (remember 6/8 is a duple meter) and think of it as compound and you will get ticks on the first and fourth 8th notes (“One, Two | One, Two”), and you just think about the other divisions (“One+a, Two+a | One+a, Two+a”). To make it back to 2/4, just shift to thinking “One+, Two+ | One+, Two+” and that solves the problem with no adjustments on the metronome itself.

I’ve never really found the metronome’s built-in subdivisions to be that useful. Usually you want to set the metronome to at least one subdivision higher than the lowest one you are counting. Often it’s best to have it do the “big beats” and handle all the subdivisions mentally. If you are going very slowly then you might want to tick in the middle level of the subdivisions (see Counting Subdivisions if this sentence was confusing!). Here’s another trick that you can use with any metronome app because it just relies on single ticks - if you are working in 4/4 and you want the metronome to be using 8th note ticks, just double the tempo and think of the tick as being an 8th note (or halve it to go from 8th note to quarter note). To go from dotted quarters to 8ths (in 6/8, for example), just multiply the dotted quarter tempo by 3, or divide by 3 to go from 8ths to dotted quarters. It doesn’t matter what unit the metronome tells you it is doing, ultimately they are just ticks and you can make them what you want just by thinking of them differently, particularly if you disable the downbeat accent.

Something else you might consider in certain contexts is going all the way to “fancy features” and using a drum machine rather than a metronome. In certain popular music styles, especially where drum set is a standard instrument in the actual music, this can be a more useful or more fun way to practice with a groove, especially if the drum machine has any groove settings that take it away from precisely metronomic and you can try playing with something closer to a real “feel”. It may not be as useful for Musicianship class exercises or classical practice, but it’s something to think about. The classical version of this might be to try playing with recordings of a piece you are working on, but this requires you to already be at a level with the piece to play it at performance tempo, and there’s no easy way to ramp up slowly. You can adjust the speed of audio playback, but the artifacts this introduces can still be problematic and you still don’t usually have a fine-grained ability to ramp up slowly.

By the way, Estrin mentions in his video I link above that the original mechanical metronomes don’t increment in 1 BPM units. Here’s a table with the standard mechanical metronome speeds. It’s a good idea when increasing speed slowly with a metronome to boost the speed a few BPM at a time, not literally one BPM at a time. You won’t notice much difference from 70 BPM to 71 BPM, but you will from 70 BPM to 74 BPM. I often use 5 BPM increments when I’m doing that practice method unless it starts to feel too fast, in which case I back off a little. The standard speeds referred to above might be a good place to start, especially once you find your limit and you want to increase things a little at a time from there.

Finally, if anyone wants to know what I use, I actually frequently use the built-in metronome in ForScore on the iPad when I’m reading sheet music in my ForScore app. It’s a relatively simple metronome, but as I’ve just been explaining you can do everything you need to with an app that just ticks with one sound. This one does default to accenting the downbeat in 4/4 and you can change the meter, but it doesn’t do subdivisions. One of the nice things it does is allow you to tap a tempo if you know what you want but not what the number is. It’s easy to change the number in several ways (in 1 BPM increments). So this metronome does everything you’d need to do with one. (If you’re wondering how to disable the accent, set the meter to 1/1, and if you’re wondering just how to start it, tap on the “Audible” button).

The other app I use when I’m not in ForScore is the metronome feature in TE Tuner on the iPhone. This is a nice utility app that has a visual tuner and “pitch pipes” so you can tune by ear, an audio analyzer function, and a metronome. This is one of the fancy metronomes, though I just realized they have a “simple” mode. But it defaults to the advanced mode, and it does all the subdivisions and different meters and all those things. I just use it like a simple metronome anyway. Sometimes I play with the accent turned on if it’s relevant to what I’m doing, but I’m just as likely to disable the accent and just use it as a plain single tick metronome as I’ve described above. I never use the subdivisions unless I’m messing with it to see what it can do.